16 Rampart Road

Rita Lynn Jacob

I was born on 7 July 1948 at the Cedars Nursing Home in Manor Road and taken to 16 Rampart Road ten days later; this being the home of my parents, Ken and Muriel Jacob, and my father’s sister, Nora. Here, I was to live until 1969; the buildings on our side of the road having been selected for demolition as part of the Inner Relief Road scheme.

The bulldozers, however, destroyed more than bricks and mortar; a close community also torn being apart as the residents were rehoused all over Salisbury. The remains of Number 16 must now be lying beneath the concrete and tar of Churchill Way but, in my memory, the houses and their occupants live on!

The Building

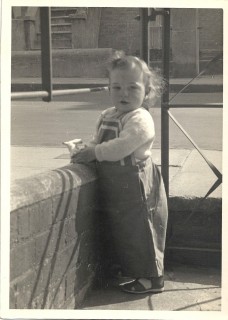

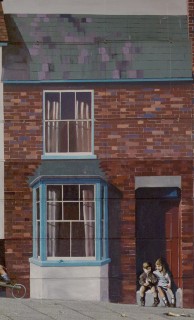

Built at the turn of the century, Rampart Road followed the line of the old city ditches; the terrace houses differing in style because of the rise and fall of the land. Number 16 was one of a group that had front doors up to forty five centimetres below pavement level, a low brick wall enclosing a small paved area around a bay window. Afraid that I would run out into the road, Dad added some railings and a gate; Mum finding it even more difficult to manoeuvre the pram up and down the drop whenever she went out.

At the rear of the building, however, the garden was less than two metres below the back bedroom window and was reached by climbing eight steep brick steps located at the end of a yard. Near the steps, was the only toilet; nearly all the houses on our side of the road being without bathrooms. This draughty facility had no lighting and its roof space was a haven for large spiders; these often scurrying down the walls and across the floor in search of another place to lurk. For this reason, we usually carried a torch when it was dark, also grabbing a coat if it was very cold or wet.

Like most of the properties in Rampart Road, Number 16 had a hallway leading to a sitting room and a separate dining room. With a bay window overlooking the road, the sitting room was the largest room in the house and, up until 1946, had been my grandmother’s bedroom. After her death, it never reverted to its intended use, partly because it was difficult to heat. Instead, it became a playroom where Dad kept a large tank of tropical fish and most of the toys belonging to my sister and myself were stored.

The dining room was smaller but could still accommodate two easy chairs as well as a dining room suite and a sideboard. Three cupboards, two of which were under the stairs, provided additional storage; tinned and packaged food being put into the one that was nearest the kitchen as there was no larder in the latter. We spent most of our time in this room as it was possible to burn a fire in the grate and it had the best lighting; a radio and, later, a television, being installed in the corner by the window.

For many years, we referred to the kitchen as ‘the scullery’; the fittings initially consisting of a deep porcelain sink, a gas cooker and a large copper which Mum disliked using. Moreover, in the late nineteen forties, it may not have been wired for electricity as I can remember Dad threading cables through the ceiling so that he could replace the copper with a refrigerator that his workplace no longer wanted. Certainly, there was no piped hot water until an immersion heater was put over the sink; kettles having to be boiled every time we wanted to wash our hair or have a bath in the long tin tub that hung on the fence outside.

The kitchen could only be accessed from the dining room, the other door opening on to the yard which had no back entry. Therefore, when the coalmen called, sacks had to be humped through the hall and dining room as well as across the kitchen itself, the coal house door being in the far wall. On wet days, Mum hastily put down sheets of newspaper; otherwise there would be a trail of muddy footprints leading from the front door and over her polished floors and carpets. This happened too when the gas meter was read, the latter being located at the bottom of the largest dining room cupboard.

The stairs at the end of the hall led up to a split landing and three bedrooms; the largest being the one over the sitting room. For a number of years, my sister and I had to share this room with our parents as my aunt had the bedroom overlooking the yard and the smallest one was not fit for habitation, needing extensive repairs to the walls and ceiling. Nor was this the only part of the house that was dilapidated, Mum believing that she had moved into a slum when she married Dad.

A Tenant’s Nightmare

Dad and Nora had lived in Greencroft Street when they were small but, by the time they were young adults, they and their widowed mother, Maud, had moved into a modern council house in Wessex Road. At some point, however, they decided to relocate to Rampart Road, both finding it increasingly difficult to push their wheelchair bound mother up the steep hills leading to the council dwellings. Like my mother, they were also making a retrograde step when Number 16 became their home!

The majority of houses in Rampart Road were rented from private landlords who often owned three or more properties. In theory, they were the ones who were responsible for structural repairs while the tenants were expected to maintain the interiors. For some reason, this had not happened in Number 16, although Numbers 12 and 14, owned by the same landlords, were in a much better condition throughout.

Working and looking after an ailing mother, Dad had been unable to do much about the décor; there also being a shortage of materials during the war years. Nevertheless, the one thing his wife was not prepared to tolerate was the old fashioned toilet, boxed round with maggot ridden wood; this soon being replaced by a new pan, seat and cistern. The state of the landing and stairway, another bone of contention, took a lot longer to rectify; the peeling dark grey wallpaper being canvas backed and very unpleasant to remove.

By the time I was eight, my father had modernised the kitchen and redecorated most of the house; only the back bedroom remaining untouched. As the ceiling of this room was now in danger of collapsing, Mum wanted to contact the landlords but Dad would not allow her to do so; instead knocking down the loose plaster from outside the window. Fortunately, the sloping roof of the coalhouse and toilet below must have been much stronger than it appeared as Dad had to clamber over the slates in order to reach his perch on the window sill; the door of the bedroom having been sealed to prevent dust filling the house.

In addition to renovating the house, my Dad had to find time to sort out the garden which was little more than a patch of bare earth with two straggly flowerbeds and Invicta’s factory wall as boundaries. It is possible that this central area had once been a lawn but Dad decided it would be more practical to concrete it over, adding random lines so that it resembled crazy paving. He then made raised flowerbeds using bricks that he had moulded himself, the one nearest the back bedroom being turned into a rockery. As a final touch, a ‘lean to’ greenhouse was erected against the factory wall; the part of the flowerbed that ran beside it being given to me. This, I filled with plants bought from the Women’s Institute stall in the market; the London Pride still flowering in my garden forty years on.

The Impact of Traffic

Like the other children who lived in Rampart Road, my sister and I were not allowed to play outside on the pavement as, with the growth of motor transport, it had become much too dangerous to do so. Therefore, until the garden had been worked on, we had to play either inside the house or out in the yard where Dad had rigged up a swing. Yet, in many ways, these restrictions made us more inventive, the area under the dining room table and chairs becoming a dolls’ hospital or palace while the stairs were used as tiers of theatre seats.

For safety reasons, I was also escorted to and from St. Martin’s Infants School, Mum having to make the journey four times a day while I was there. When I moved up to the Juniors, however, I was allowed to walk down to Flo Lanning’s sweet shop by myself, my mother trusting me to keep to the inside of the pavement. Later, this privilege was extended to include Percy Churchfield’s Dairy and Coleman’s grocery shop but I was never allowed to cross Milford Street or St. Ann Street without an adult until September 1959 when I had to make my own way to South Wilts Grammar School.

Cars, lorries and the Number 37 bus from Southampton were not the only hazards we faced in Rampart Road; it then being the practice to drive cattle along the roads between Milford Goods Station and the market. With Percy Andrews, the cow walloper, following behind, the animals could break from a trot into a full gallop; it also not being unusual for a cow to stray into a front garden and peer through the window! On market days, we rushed home from school, even Mum running down the road if we heard the sound of pounding hooves and Percy’s hollering in the distance!

Riverside and the Greencroft

Going to the play areas in the Riverside Gardens or the Greencroft, meant crossing even more roads so my sister and I could only visit these if someone was willing to take us. Also, when I wanted to ride my bike, I had to wait for my father to come home; Dad keeping a firm grip on the handlebars and saddle as I rode along the pavements and down Friary Lane to Riverside. This was a lovely place to be on a warm summer’s evening, allotments and a swathe of grass then occupying the area between Wiltshire College and the Harnham roundabout. Moreover, the play equipment was safer for small children although, later, I grew to love the steep slide and conical roundabout in the Greencroft, not caring how fast or high the latter went.

Special Occasions

Although spring is now my favourite season, I loved autumn as a child; the countdown to Christmas beginning with the arrival of Salisbury Fair in October and the appearance of fireworks in Noyce’s Newsagents. Using money given to us by our aunt, we only bought a few at a time, choosing those with pretty names like Silver Fountain and Golden Rain as they lasted longer than the ‘bangers’ which quickly fizzled out. Dad set these fireworks off at the top of the brick steps while the rest of us watched in the yard, Jill and I being given sparklers to hold. Only once did we go to Greencroft on Bonfire Night, our evening being spoilt by youths throwing fireworks at the feet of families gathered at Kelsey Road corner. It was a shame that this irresponsible element was beginning to creep in as the bonfire was a tradition going back decades and fondly remembered by the older residents.

Christmas was the most magical time of all; tissue wrapped tangerines, colourful boxes of dates and nets of nuts often being the first seasonal items that we saw. Christmas trees were put on sale later, Jill and I pestering our parents until one was bought and put into the bay window; other residents gradually doing the same. None of these trees were themed or matched the house décor, many of the decorations also being old and a bit tatty. Yet, when they were lit at night, Rampart Road became a fairyland.

On Christmas morning, wrapped up in thick dressing gowns, Jill and I were given stockings to open, these containing small items like sugar mice and colouring books. Then, Dad staggered upstairs with two pillowcases full of presents, claiming that Santa Claus had left them in the coal house. By sprinkling coal dust on the pillowcases and himself, he managed to fool us for a number of years although we did begin to wonder why we usually got most of the toys that we had liked in Southampton shops!

Toxic Haze

Meanwhile, the summer months were becoming less idyllic, the amount of traffic using Rampart Road increasing dramatically each year. At weekends, long queues stretched in both directions, anyone wishing to cross between 9am and 6pm often having to clamber over or squeeze between bumpers. Petrol still being leaded, a toxic haze shimmered above the stationary vehicles; these fumes filling the hallway and deposing gritty particles on any ledge or sill at the front of Number 16. Yet, it was the vibrations that probably did the most damage, the house foundations having been already weakened by the military convoys that had passed through during the war. By the 1960s, there was little but air beneath the floorboards in the bay window, we all holding our breath when the Christmas tree was placed on the table as both could have disappeared into the void below.

Life in Rampart Road had a pattern and permanence but, when I was about twelve, my parents began to talk about moving; Dad now being the Chief Engineer at Odstock Hospital. Unfortunately, however, a dream of owning a property in the Coombe Road area was never realised, Dad dying suddenly in September 1961. Therefore, it was my mother who had to cope with the problems and uncertainty when plans for Churchill Way were finalised; the latter proving more devastating than anyone could have imagined.

I do not know when the rumours about a relief road first started but I think most residents initially believed that it would circumvent Salisbury, part of it leaving the London Road before it reached Laverstock and joining the Southampton Road just past Alderbury. Also, by the time the actual route was made public, it was too late for any form of effective protest; the scheme beginning with the redevelopment of The Friary not long after my father’s death. For many of the people who lived in the area, the construction of Churchill Way is still a controversial and emotive subject; the spur road to a non-existent car stack in Brown Street wasting thousands of pounds of public money.

Another misconception was that the residents of Rampart Road would be rehoused together, either in The Friary or Donaldson Road. Instead, a small block of flats in Tollgate Road was designated, those living at the St. Ann Street end having to move out months before these dwellings were completed. Those who owned their own homes were in a particularly invidious position; knowing that any money they received under a Compulsory Purchase Order would be insufficient to buy a similar property – or one at all. Therefore, owners and tenants were forced to move into council accommodation, the latter still carrying a social stigma in the 1960s.

July 1969 and Beyond

Between September 1966 and July 1969, I was in Oxford training to be a teacher; being less affected by the demolition than my mother or my sister. As we did not want to be rehoused in a flat, we were allocated an older council property in Harnham; moving several weeks after I left college. Strangely, however, this was another Number 16 with dodgy wiring, out dated kitchen and overgrown garden. DÉJÀ VU!

On the morning we moved, I left Number 16 before the removal van arrived as I was working in M&S during the holiday. I never returned, catching the Number 55 bus out to Harnham at the end of the day. The compensation we received for the enforced move was minimal, about £10 being allowed for each room. Out of this, we had to buy floorcovering for most of the house and an electric cooker, the road not being connected to a mains gas supply.

Although my aunt continued to live in the area, having moved out of Number 16 several years before, I did not walk along our part of the Rampart Road again until the summer 1975 when I had to visit one of the remaining houses. After that, I only drove past occasionally; it not being until the interview day at St. Martin’s that I actually stood opposite the site of Number 16. Suddenly, I felt bereaved and bitter, there being nothing tangible left of my childhood home or the community in which I lived, only a horrible concrete wall and a road that should not have been constructed!

No Comments

Add a comment about this page