The First World War : Civilian Life

Rita L. Jacob

The information relating to the First World War is not always specific to the Milford Street Bridge area or even to Salisbury; measures such as the introduction of a blackout in 1917 affecting the whole population. At the other end of the spectrum, there is that pertaining to a particular house or family; the fact that three casualties came from 38 Rampart Road being an example.

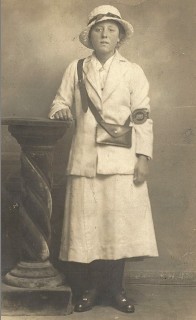

Between 1914 and 1918, Invicta workers produced leather for thousands of army boots while Arthur Maidment’s father made field kitchens for the Canadian army; probably at Farrs the coach-builders in Brown Street. Sources, however, have little about female employment during the period, other than nursing and working on the land; the Women’s Land Army having schools at Longford Castle and Wilton House. Nevertheless, as in other parts of the country, it is likely that women took over some jobs previously done by men; young Rose Gardner of Greencroft Street becoming a telegraph girl, an unpopular occupation at the time.

Towards the end of the war, fear of air raids, the introduction of a blackout and food shortages made life difficult; the latter becoming so severe during the winter of 1917/1918, that a communal Soup Kitchen was set up in the Lear Memorial Rooms. Those who used it, brought their own bowls or basins which were filled from a tap attached to a pipe in the wall. The soup was then either taken home or eaten outside in Gigant Street, trestle tables and benches having been set up for this purpose.

Despite their own hardship, people still did what they could to help those who were even worse off. Members of the Salisbury Division Red Cross Voluntary Aid Detachment, including Arthur Maidment’s father, met ambulance trains and ferried the wounded to various military hospitals; a continuous supply of garments and equipment being provided by Queen Mary’s Needlework Guild as well as parcels for our fighters. Also, when air raids began, various items were collected for fleeing Londoners; these, including Arthur Maidment’s wicker pram, being stored in the premises once occupied by the Rainbow Laundry.

The Aftermath

When the Armistice was announced in front of the Guildhall, the mayor felt he could say little more than ‘thank God the war is over’. Unfortunately, this declaration was followed by an outbreak of influenza; Arthur Maidment observing ‘More died from this scourge than were killed in the war’. Perhaps for this reason, peace celebrations were not held until the following July; children from Salisbury’s infant schools having a Peace Tea in Dr. Bourne’s field and older children taking part in a pageant of Salisbury’s history two days later. Finally, in February 1922, Tom Adlam, who had received a Victoria Cross for bravery during the Battle of the Somme, unveiled the city’s war memorial in the Guildhall Square; this remaining in situ despite recent attempts to move it!

For thousands of families, however, the suffering did not end on 11 November 1918; sometimes being perpetuated through several generations. Having been a prisoner of war, Phyllis Maple’s father was malnourished and unable to find work for two years while John Evan’s family was affected by his unpredictable behaviour after being severely wounded. Walter Jacob’s children, however, were bereavement victims, his widow, Maud, becoming ill and increasingly dependent on them after the loss of ‘her Wally’. As a result, her son, Kenneth, did not marry until after her death in the 1940s, his sister remaining single and lodging with the couple in what had been her family home.

Postscript

Nora Jacob always maintained that her father was dropped while being carried out to a military ambulance, on bus journeys pointing out a large country house to which he was taken. It is something of a mystery why Walter was at home at this point in time. Had he been sent home after becoming ill or had he contracted pneumonia while on leave?

Arthur Maidment, who is mentioned several times above, was born in Culver Street on 22 September 1914. His book, I Remember, covers his life in the city between 1917 and 1926, including the time he spent at St. Martin’s School. If one wants a detailed account of what the area was like during this period, it is a book worth reading!

No Comments

Add a comment about this page